November 11, 2019

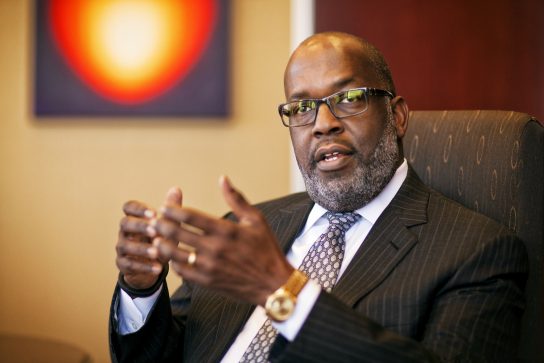

(Photo: Gary Parker)

Bernard J. Tyson, the chairman and CEO of Kaiser Permanente, has unexpectedly died, Kaiser officials announced on Sunday. He was 60 years old. He passed away in his sleep.

Tyson was a monumental figure in health care, a person who dedicated himself to the notion that it was both possible and morally correct to make sure everyone had what they needed to be as healthy and productive as they could be. And he was a personal inspiration to me, ever since our first conversation years ago.

He cared deeply about the communities left behind. He was a tireless innovator who championed the idea of equity in medicine and embraced data-driven solutions which aimed to integrate mental and physical health and eliminate race-based disparities. "[W]e now know that the social determinants of health—many of the other categories that we haven't really addressed concretely—impact a person's health much more than medical care," he told Fortune editor-in-chief Clifton Leaf last year.

"One of the big ones is the thing called the zip code. Literally, you can see the differences in the life expectancy in one zip code versus another."

Tyson called this his"total health agenda." Last spring, KP launched a $200 million "impact investment fund," designed to help them better understand and address the needs of underserved communities.

But Tyson's greatest strength may have been his spirit.

"I have the opportunity and the obligation to change the narrative around complex conversation like race that help us work together toward common objectives," Tyson told me during our first-ever interview.

He was a main figure in Leading While Black, my 2016 feature that explored the many barriers keeping Black men out of the executive ranks of Fortune 500 companies. As the CEO of what was then a $60 billion company, he regularly experienced the cognitive dissonance of being The Man in the C-suite and a suspect on Main Street, he said. And he had been personally gutted by the image of Michael Brown's lifeless body sweltering in the Ferguson, Mo. heat. "It was the image of an African-American kid, shot down and left in the street," he told me. "Regardless of how it happened, you personalize that."

At significant personal and professional risk, he began to write and talk about race, knowing that it often made other powerful people uncomfortable.

"We have to be able to tell the truth about these things," he told me early and often.

My colleague Clifton Leaf has done the world a tremendous service with his heartfelt assessment of Tyson’s legacy. Tyson had become an important figure in the Fortune conference community, and he rarely missed an opportunity to take the stage or a mic to share his work and truth.

"To say that Bernard Tyson was good-natured, which surely he was, would miss the point, however. His nature, simply put, was good—and he felt an obligation to be candid about where the world felt short in that respect.

He was bold and forthright, on matters ranging from the cost of health care ("It was unaffordable, period," he'd say) to homelessness ("The narrative that it's okay to keep stepping over the homeless and going about our business in the richest country of the world is just something we cannot accept.") to what it's like to be black man in America."

Please read and share, if you can.

And do take a moment to process the fact that Black men have among the lowest life expectancies of any demographic group in the U.S.

If you believe that raceAhead does good work, or that Fortune has done an important thing by establishing a race beat and deepening our coverage online, in print, and in our conferences, then Bernard J. Tyson deserves part of the credit.

Because of his own candor and commitment to telling all the truths, he consistently made it possible for his peers to be courageous, too. And that courage extended to me. Bernard was one of the few people I spoke to in the early days of writing about race in America who understood how ugly the path could be, and the kinds of risks I'd be facing moving forward.

That acknowledgement made all the difference for me.

Bernard never missed the chance to let me know that our work wasn't going unnoticed. It’s become clear from all the online tributes pouring in that he did this for many, many people.

Affirmation was his superpower.

"I've learned never to tell people that I appreciate what they did," he told me once. "I always tell them, 'I appreciate you.' I want them to know that I see them for who they are. That they are more important than a task or a job description or anything they did for me."

Bernard J. Tyson, I appreciate you.

Ellen McGirt

@ellmcgirt

Ellen.McGirt@fortune.com

No comments:

Post a Comment